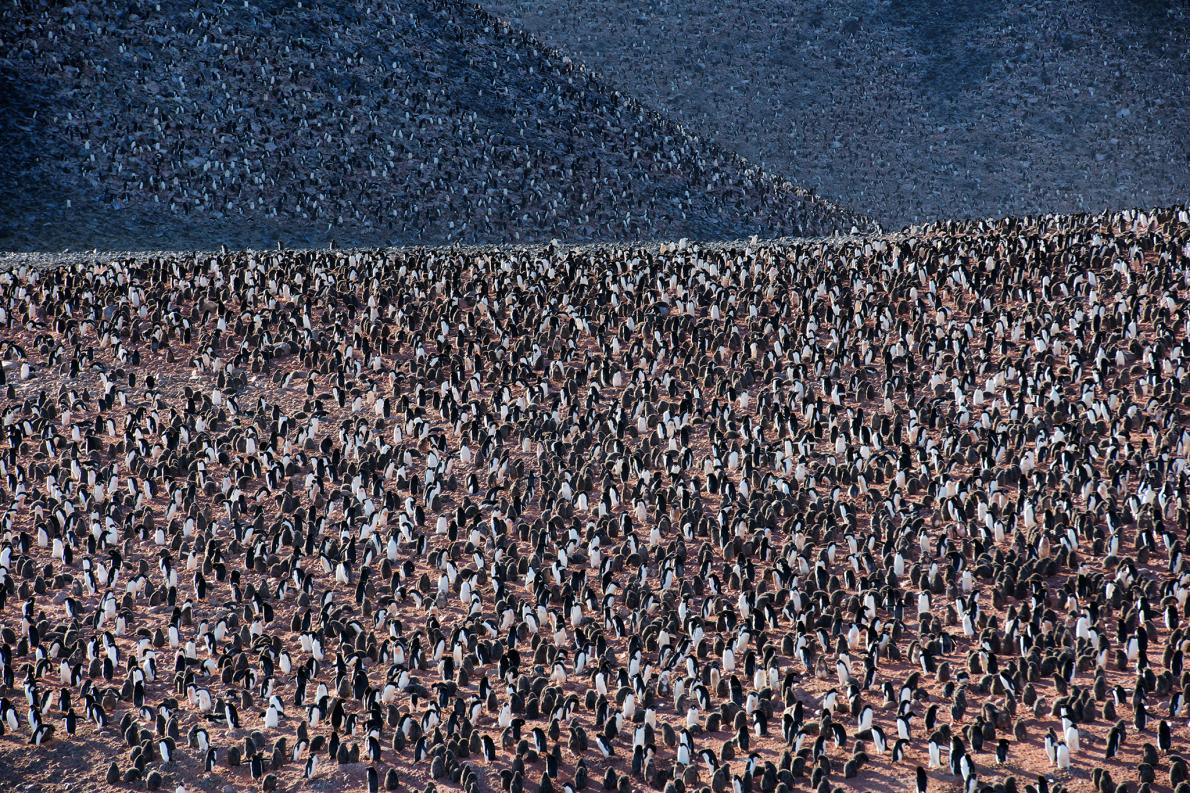

Antarctica Could Lose Most of Its Penguins to Climate Change

Source: news.nationalgeographic.com

A new study finds significant impact, and a possible silver lining, for the iconic birds over the next century.

By

Published Wednesday in Scientific Reports, the study, led by oceanographer Megan Cimino, found that up to 60 percent of the current Adélie penguin habitat in Antarctica could be unfit to host colonies by the end of the century.

The Adélie penguin is one of two true Antarctic penguins—the other being the emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri)—and it inhabits the full extent of the continent. The penguins nest on land during the austral (southern) summer, and migrate during the winter to the edge of the sea ice, where they are able to feed at sea.

Climate’s Specific Impacts

Many Antarctic researchers believe that climate change will affect penguins through two primary pathways: the quality and availability of food and nesting habitats.

Warming seas could reduce the abundance of penguins’ prey, resulting in changes in the composition of the birds’ diets.

Cimino explained the threat to the Adélie food supply: “Changes in [sea] ice and temperature can cause changes in the food, krill and fish.” In some areas, she continued, “the fish populations have gone down a ton, so their major diet in those areas is krill. In other areas, these penguins eat more fish, which are a more nutritious food source.”

Climate change could also reduce the quality of many penguin nesting sites by precipitating changes in local weather. Antarctica’s climate is generally cold, dry, and harsh, but warming could yield unprecedented rain, or prematurely melt snowfall, creating puddles on the ground.

According to Cimino, this could be bad news.

“For penguins who lay their eggs on the ground … rain and puddles are bad because eggs can’t survive when they’re lying in a pool of water. Chicks that don’t have waterproof feathers can become wet and die from hypothermia.”

Using a combination of field survey data and high-resolution satellite imagery, the researchers were able to stitch together 30 years of colony data, from 1981 to 2010, at sites ringing Antarctica. Looking at the year-to-year data, the researchers were able to identify population trends at each colony site for the full 30-year period.

The scientists found diverging trends at different sites. Some colonies, like the closely monitored population near Palmer Station, a United States research hub in northern Antarctica, saw declines of over 80 percent. Other sites were stable, and some even had growing colonies.

Tellingly, the sites that experienced population declines over the study period were often sites that experienced novel climates, or conditions outside the range of historical observations.

The researchers used statistical models to derive a relationship between colony population trends and climate, represented by sea surface temperature and sea ice concentration. This relationship was incorporated into future climate projections to estimate the quality of penguin habitat at the end of the century.

David Ainley, a senior biologist with the ecological consulting firm HT Harvey & Associates, confirmed that the research is consistent with past findings; however, he emphasized that the loss of sea ice may ultimately be a greater threat than warming sea surface temperatures.

“The Adélie penguin is a sea ice obligate and only occurs where there is sea ice for a good part of the year…Where sea ice is disappearing in the northern Antarctic peninsula, the Adélie penguin is disappearing.”

Silver Lining?

Despite this dire prediction, Cimino and her colleagues did find a silver lining in their research. While the projections look grim for the penguins at northerly latitudes, the study did identify several refugia where the penguins could continue to thrive.

Climate refugia are locations where animals could survive periods of adverse climate, safe havens that could support them in an otherwise uninhabitable world.

In the face of a warming climate, the Adélie penguins may find refuge in the Ross and Amundsen Seas. These areas are thought to have been glacial refuges in the past, and climate projections suggest they may provide refuge again in the future.

Given the disjointed nature of Antarctic politics—30 countries operate research stations on the continent, and seven nations maintain territorial claims—consistent resource management can be difficult to achieve. Cimino believes it is imperative to prioritize conservation in the places that could shelter the Adélie penguins from climate change. Specific actions could include the establishment of marine protected areas and the fishing restrictions around projected refugia.