‘Death Awaits’: Africa Faces Worst Drought in Half a Century

Source: www.spiegel.de

By Bartholomäus Grill

The worst drought in half a century has stricken large parts of Africa — a consequence of El Niño and high population growth. More than 50 million people are threatened by hunger and few countries have been hit as hard as Ethiopia.

Herdsman Ighale Utban used to be a relatively prosperous man. Three years ago, he owned around a hundred goats. Now, though, all but five of them have died of thirst at a dried-up watering hole, victims of the worst drought seen in Ethiopia and large parts of Africa in a half-century.

Utban, a wiry man of 36 years, belongs to a nomadic people known as the Afar, who spend their lives wandering through the eponymously named state in northeastern Ethiopia. “This is the worst time I’ve experienced in my life,” he says. On some days, he doesn’t know how to provide for himself and his seven-member family.

“We can no longer wander,” Utban says, “because death awaits out there.” For now, he’ll have to remain in Lii, a scattered little settlement in which several families have erected their makeshift huts. Lii means “scorching hot earth.”

‘First the Livestock Die, Then the People’

Since time immemorial, shepherds have wandered with their animals through the endless expanses of the Danakil desert. They live primarily off of meat and milk, and it was always a meagre existence. But with the current drought, which has lasted for over a year, their very existence is threatened. “First the livestock die, then the people,” Utban says.

The American relief organization USAID estimates that in Afar alone, over a half million cattle, sheep, goats, donkeys and camels have perished. Reservoirs are empty, pastures dried up, feed reserves nearly exhausted. With no rain, grass no longer grows. Many nomads are selling their emaciated livestock, but oversupply has led to a 50 percent decline in prices.

Currently, millions of African farmers and herders are suffering similar fates to Utban’s. The United Nations estimates that more than 50 million people in Africa are acutely threatened by famine. After years of hope for increased growth and prosperity, the people are once again suffering from poverty and malnutrition.

State of Emergency

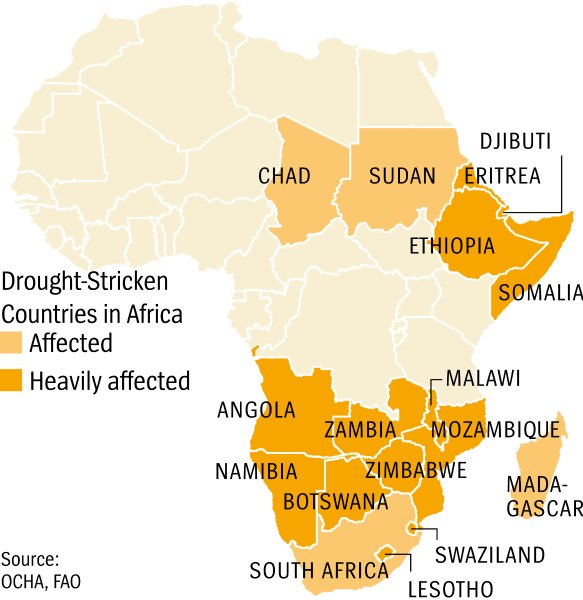

The governments of Malawi, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Lesotho and Swaziland have already declared states of emergency, and massive crop losses have caused food prices to explode in South Africa. Particularly hard stricken are the countries in the southern part of the continent as well as around the Horn of Africa, Somalia, Djibouti, Eritrea and especially Ethiopia.

Meteorologists believe the natural disaster is linked to a climate phenomenon that returns once every two to seven years known as El Niño, or the Christ child, a disruption of the normal sea and air currents that wreaks havoc on global weather patterns. The El Niño experienced in 2015-2016 has been particularly strong.

Mohamed Nasir is the clan elder in the Lii nomad settlement. He says he’s never heard of El Niño before. “The lack of water is our main problem — that’s why we’re fighting for our lives.” Nasir doesn’t have any explanation for why the weather has gone crazy. For why drops of rain no longer fall from the ice-gray skies here in the mountains, while only a three days’ walk away, the plains are flooded. For why his home region has been plagued by periodic droughts for more than eight years now. “Perhaps it’s God’s will,” he says.

Nasir has just finished praying for rain, bending over in the dust according to Muslim ritual, with grains of sand still stuck to his forehead. He’s 61 years old, but the worry lines in his face make him look a lot older. He sits in the shadows of a camel thorn tree, looking east. A hot wind blows from the Red Sea out over the karstic, grayish-brown countryside. Over the horizon, the empty promise of a few cirrostratus clouds can be seen. He’s been waiting for rain for a year now.

An Image at Odds with Emerging Ethiopia

This year’s crisis is worse than the one that befell the area in 1985, Nasir says. Back then, the most catastrophic year in Ethiopian history, around a million people died of famine.

Nasir says there have already been deaths this year in his clan’s region. He points to the mountainside behind and says, “Nine children are buried there.” Other herders also speak of the first starvation victims in Afar, but it isn’t possible to confirm the reports.

The government in Addis Ababa denies the deaths. It wants to overcome Ethiopia’s image as a country eternally beset by famine and instead present itself as an emerging nation. The Ethiopian economy, after all, is among the fastest growing in the world, with annual growth rates as high as 10 percent in recent years.

Ethiopia, one of the world’s poorest countries, has transformed itself into a successful development dictatorship based on the Chinese model. It wants to achieve middle-income country status by 2025 and establish itself firmly as an emerging nation. Pictures of starving children with large, sorrowful eyes do not fit with that image.

The country’s boom is visible in the capital city of Addis Ababa, which is currently undergoing an incredibly fast process of modernization. High rises and giant new districts are sprouting up everywhere, new motorways criss-cross the capital and a light-rail system has even been built — the first anywhere south of the Sahara. Numerous new industrial enterprises are located at the city’s outskirts, where they produce textiles and leather goods for the global market.

Covering Up the Scale of the Disaster

For a long time, the government insisted that the country could handle the situation on its own. Indeed, Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn first requested assistance from the international community in March. But international aid organizations were also ordered not to speak publicly about the true scale of the disaster, the liberal magazine Addis Standard recently reported — a newspaper that is viewed with some skepticism by the government.

The authoritarian regime doesn’t tolerate criticism: Members of the opposition are persecuted and unruly journalists imprisoned. Nor are oppositional voices to be heard in parliament, where the governing Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) holds 100 percent of the seats. The party liberated Ethiopia in 1991 from the socialist terror rule of Mengistu Haile Mariam, but itself likewise acts with a heavy hand.

The country’s Western allies ignore the continuing human rights violations because Ethiopia, a bastion of Christianity, is an important military partner in the battle against Islamist terror on the Horn of Africa.

In praising itself, the government often points to the lessons learned from the 1984-85 famine. In response, Ethiopia set up a disaster early warning system and created emergency grain reserves. The country built dams, irrigation systems and roads. Around 7 million small farmers now receive crisis aid through a state safety net.

Esubalew Meberate is proud of these achievements. As the head of an administrative district with 257,000 residents, he’s responsible for 37 municipalities, 22 of which have been affected by the drought. He receives visitors in his office in the city of Gohala, high in the mountains in the state of Amhara. Meberate wears a stylish black leather jacket and a white casual shirt. He’s a typical representative of the ruling class: young, power conscious and a tad arrogant. He admits that ensuring water supply is the greatest challenge. The problem is that a dearth of transport routes makes it impossible for tanker trucks to reach all the villages. Still, he says, the government is working to address it. “Our economy is growing despite the drought and our agricultural potential is nowhere near exhausted.”

‘We No Longer Have Enough to Eat’

Yet even as the elite in the capital city enthuse about economic growth, in the mountains of Amhara, the Ethiopian heartland, people like farmer Destay Zegeye are suffering. “We no longer have enough to eat,” she complains. Last year, she says, the belg, or short rainy season, failed to materialize. Neither did kiremt, the long rainy season. Zegeye says she was only able to harvest a hundred kilograms of teff, the country’s most important food grain. She was able to keep two sacks for her seven-member household — far too little for survival.

Zegeye, 36, wears a tattered, patchwork dress with a cross dangling from her neck. She walks across the field in front of her hut, a half-hectare (1.2 acre), dry and dusty square littered with stones.

She is struggling to get her family through this period of struggle. Sometimes her husband earns a few birr as a day laborer for a government employment creation program focusing on the construction of schools, roads and storm water tanks. He also recently sold two of their four oxen. The family also gets rations from the government — 15 kilograms of grains per month and household. Somehow they manage to get by, but for how much longer?

All around the mountainous country, you find the same bleak image: cracked soil hard as cement, rocky fields and dried-up creek beds — no green patches for as far as the eye can see. In between are impoverished mountain villages that are constantly growing: Places like Qualisa, for example. Just 15 years ago, only 1,500 people lived here, but today a local employee of the German relief organization German Agro Aid (Welthungerhilfe) estimates that figure to be closer to 12,000. Such growth is the result of enormous settlement pressure. The once forested mountainsides have been clear-cut because of the growing population’s need for firewood and construction material.

Ethiopia Needs an Agricultural Revolution

At the same time, agricultural production has failed to keep up with the pace of population growth. Since the massive famine that struck Ethiopia in 1984-85, the country’s population has swollen from 41 million to 102 million. One-third of the population is already considered to be malnourished today: There simply isn’t enough to go around in many parts of the country.

Much of that situation is attributable to the country’s antiquated system of subsistence farming. Millions of small farmers are incapable of yielding larger harvests because of their inability to access investment capital, equipment, fertilizers and high-quality seeds. In addition, their property belongs to the state, meaning they can cultivate it, but are unable to use it as collateral on any potential loans. They thus slave away just as in biblical times, using hoes, oxen and wooden plows to till low-yield soil.

What Ethiopia needs is an agricultural revolution, but the government is doing too little to mechanize agriculture and increase productivity. In fact, it has done the opposite by clinging to its strategy of industrialization — one that includes the leasing of giant farmlands to foreign agricultural companies which then export foodstuffs in grand fashion from the country at a time when it must import hundreds of thousands of tons of wheat in order to compensate for the crop losses caused by the drought.

Will Famine Become Chronic?

There also appears to be little concern in political power circles about annual population growth of 2.5 percent. The attitude seems to be: the more people it has, the stronger Ethiopia will be. What this overlooks is that the rapid recent population increase has been eroding successes in development policy. Agriculture experts warn that if the Ethiopian population swells to 150 million people by 2035 as some are predicting, famine could become a chronic problem.

Nor is this problem limited to Ethiopia. It could also be a harbinger of further food crises in Africa. “We are simply too many people,” says Ayenew Ferede, 37, the head of a kebele, the smallest administrative unit in Ethiopia. Seven-thousand people live in his ward, and 2,000 receive government emergency aid. “People are starving because we have run out of everything — water, grain reserves, livestock feed.”

Ferede has traveled for four hours by foot here to the small town of Hamusit in the hunt for aid. He carries a heavy burden of responsibility. He, too, reports of famine deaths. “If it doesn’t rain soon, we are all going to leave.” But where will they go? “To the next kebele, to the city, across the sea to you in Europe. Someplace where there’s water and food.”

Though it has rained in recent days in some parts of the country, Ferede has little hope. “It’s too little, too late and the worst is yet to come.”