Can New York Be Saved in the Era of Global Warming?

Source: www.rollingstone.com (full text and video)

The future of America’s greatest city is at risk

It’s a bright spring day in New York, with sunlight dancing on the East River and robins singing Broadway tunes. I’m walking along the sea wall on the Lower East Side of Manhattan with Daniel Zarrilli, 41, the head of New York’s Office of Resilience and Recovery – basically Mayor Bill de Blasio’s point man for preparing the city for the coming decades of storms and sea-level rise. Zarrilli is dressed in his usual City Hall attire: white shirt and tie, polished black shoes. He has short-cropped gray hair, dark eyes and an edgy I’ve-got-a-job-to-do manner. Zarrilli may be the only person in the world who holds in his head the full catastrophe of what rising seas and increasingly violent storms mean to the greatest city in America. Not surprisingly, instead of musing about the beautiful weather, he points to the East River, where the water is innocently bouncing off the sea wall about six feet below us.

“During Sandy,” he says, darkly, “the storm surge was about nine feet above high tide. You and I would be standing in about four feet of water right now.”

As Zarrilli knows better than anyone, Hurricane Sandy, which hit New York in October 2012, flooding more than 88,000 buildings in the city and killing 44 people, was a transformative event. It did not just reveal how vulnerable New York is to a powerful storm, but it also gave a preview of what the city faces over the next century, when sea levels are projected to rise five, six, seven feet or more, causing Sandy-like flooding (or much worse) to occur with increasing frequency.

“The problem for New York is, climate science is getting better and better, and storm intensity and sea-level-rise projections are getting more and more alarming,”

says Chris Ward, the former executive director of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, the agency in charge of airports, tunnels and other transportation infrastructure.

“It fundamentally calls into question New York’s existence. The water is coming, and the long-term implications are gigantic.”

In a world of rapidly rising seas, New York is better prepared than many coastal cities. As anyone who has seen the rock outcroppings in Central Park knows, much of Manhattan is built on 500-million-year-old schist, which is impervious to saltwater.

Unlike a storm of the century, with sea-level rise the water comes in slowly and never leaves. It just keeps rising until the ice sheets are all but gone (or they reach a thermal equilibrium and stop melting). At a recent talk to engineers and policymakers in the Netherlands, Matthijs Bouw, a Dutch architect who is working on the Big U, flashed an image of New York with buildings poking out of the water like trees in a swamp.

“This is the conversation that isn’t taking place,” Bouw told the group.

Building walls around a city is an idea that is as old as cities themselves. In the Middle Ages, walls were built to keep out invading armies. Now they are built to keep out Mother Nature. Obviously, if they are built right, they work. More than a quarter of the Netherlands is below sea level; without walls, dikes and levees, much of the nation would be a kingdom of fish. New Orleans exists today only because of its enormous levees. Virtually every coastal city in the world is defended by sea walls of one kind or another. But even in the Netherlands, walls are falling out of favor.

“We are beginning to realize we can’t keep building walls forever,”

Richard Jorissen, a Dutch expert in flood protection, told me as we drove by a dike in the Netherlands one recent afternoon.

“Sometimes they are necessary, but we also realize that we have to learn to live with the water. If it is not built right, a wall can create as many problems as it solves.”

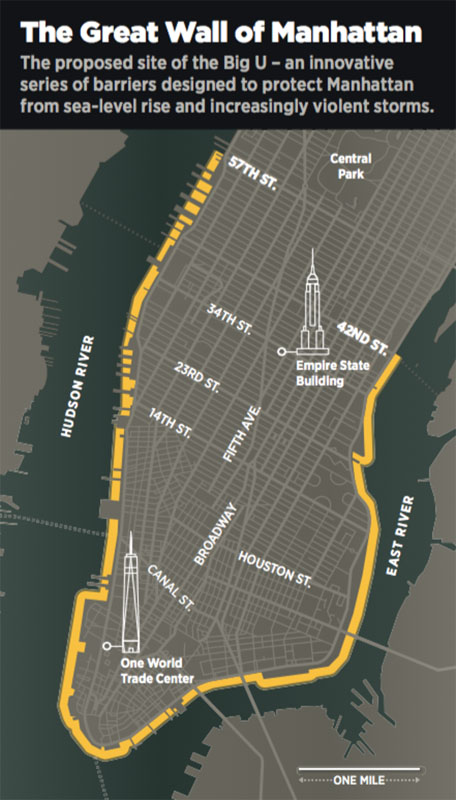

As far as walls go, the Big U is designed to be a nice one (“a wall with benefits,” as one urban designer puts it). It was one of the winning proposals in Rebuild by Design, a $930 million competition sponsored by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development that hoped to inspire the world’s best architects and urban planners to rebuild a better New York. It’s the love child of a collaboration headed by the Bjarke Ingels Group, the hot Danish firm that has designed a number of playful buildings around the globe (the firm’s design for a trash incinerator in Copenhagen includes a year-round artificial ski slope).

Rebuilding New York after Sandy was a joint city, state and federal project. Almost all the funds came from a $60 billion federal disaster-relief appropriation from Congress, which has been doled out to various state and local agencies. The federal response to Sandy was widely praised. But rebuilding from Sandy is not the same as rebuilding for the city’s long-term future. And in that, the city has had very little help from Washington, D.C., and much less from Albany. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo has put some political muscle into greening the state’s energy grid, but the reconstruction of New York City hasn’t earned much of his attention (within City Hall, many believe it is personal – Cuomo, who thinks of himself as the Big Dog in New York state Democratic politics, won’t do anything to make his archrival de Blasio look good). In the aftermath of Sandy, Cuomo commissioned a high-level study about how to make the state of New York more resilient to climate change – then hardly mentioned it again after it was complete. Some of his recent pet projects, such as a $4 billion proposal to renovate the aging LaGuardia Airport, which is located in a high-risk flood zone, make no sense in a world of rapidly rising seas.

Unlike Miami or Bangladesh, whose very existence is at risk, New York has enough money and enough high ground to ride out whatever comes this century. The question is, what kind of city will it be? Will it be a safe, livable place, alive with art and commerce, inspiring to the world?

“New York has always defined our idea of what a city is and can be,”

says Guy Nordenson, professor of structural engineering and architecture at Princeton University. Now, New York may well define our idea of urban survival in a future of rapidly rising seas.

“I have the frame of 100 years,” Geuze tells me. “Maybe eight, nine feet of sea-level rise. We can deal with that. But there will come a moment when no matter what you do, even a rich city like New York won’t be able to do anything to protect itself. When is that moment? I don’t know. But it is coming. What Mother Nature is telling us right now is, we are not in control.”

Read a full text: www.rollingstone.com